Curved Splines: A Case Study

The Problem

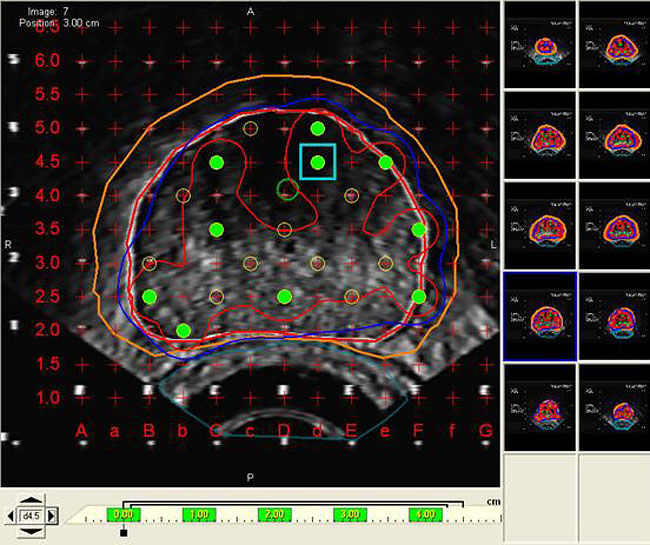

I was working for a startup making an ultrasound device for the treatment of prostate cancer.

Our device was used in conjunction with a separate application for planning brachytherapy, a cancer treatment involving inserting radioactive pellets into the prostate. The treatment planning application would determine the optimal placement for the pellets to ensure all the cancerous prostate tissue was fully irradiated, while sparing as much of the surrounding tissue as possible.

The brachytherapy planning software had very basic image recognition which was unable to handle ultrasound images.

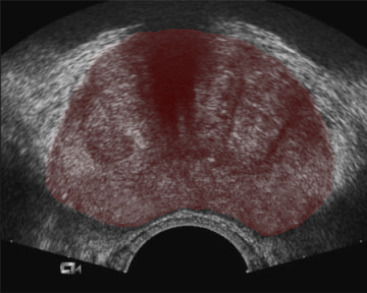

We needed to provide images with added outlines showing the contours of the prostate. The treatment planner would then use these contours for its dosimetry calculations.

Furthermore we wanted this done as quickly as possible. This process was happening while the patient was in the operating room under anesthesia and everyone else was waiting. Operating room time was expensive, with some hospitals charging $100 a minute or more.

Since we needed outlines for 8 to 10 images, the cost of this process could add up quickly.

Finding the Contours

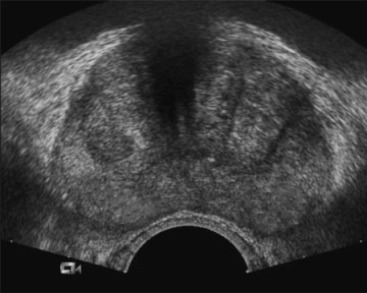

Ideally, we would have found the contours automatically in software. However, this was a few years ago and AI image processing was still pretty crude, especially for the kinds of grainy images you get from ultrasound.

Since auto-detection of the prostate was not possible, we required a physician to draw the outline of the prostate manually.

Drawing outlines could easily be done with a mouse. However, a mouse has too many crevices to sterilize easily and thus weren’t generally used in sterile settings.

Instead we opted for a medical-grade trackball.

A trackball works more or less like a mouse, but because our particular trackball was designed to keep germs out of the mechanics, it was very stiff and didn’t move as smoothly as one would prefer. The click-and-drag motion that you would do with a mouse was quite difficult and slow.

Points and Splines

Since click-and-drag wasn’t going to work, I decided to try a completely different approach. I wanted something quick and easy that wouldn’t require a much training. It should just work the way you would expect it to.

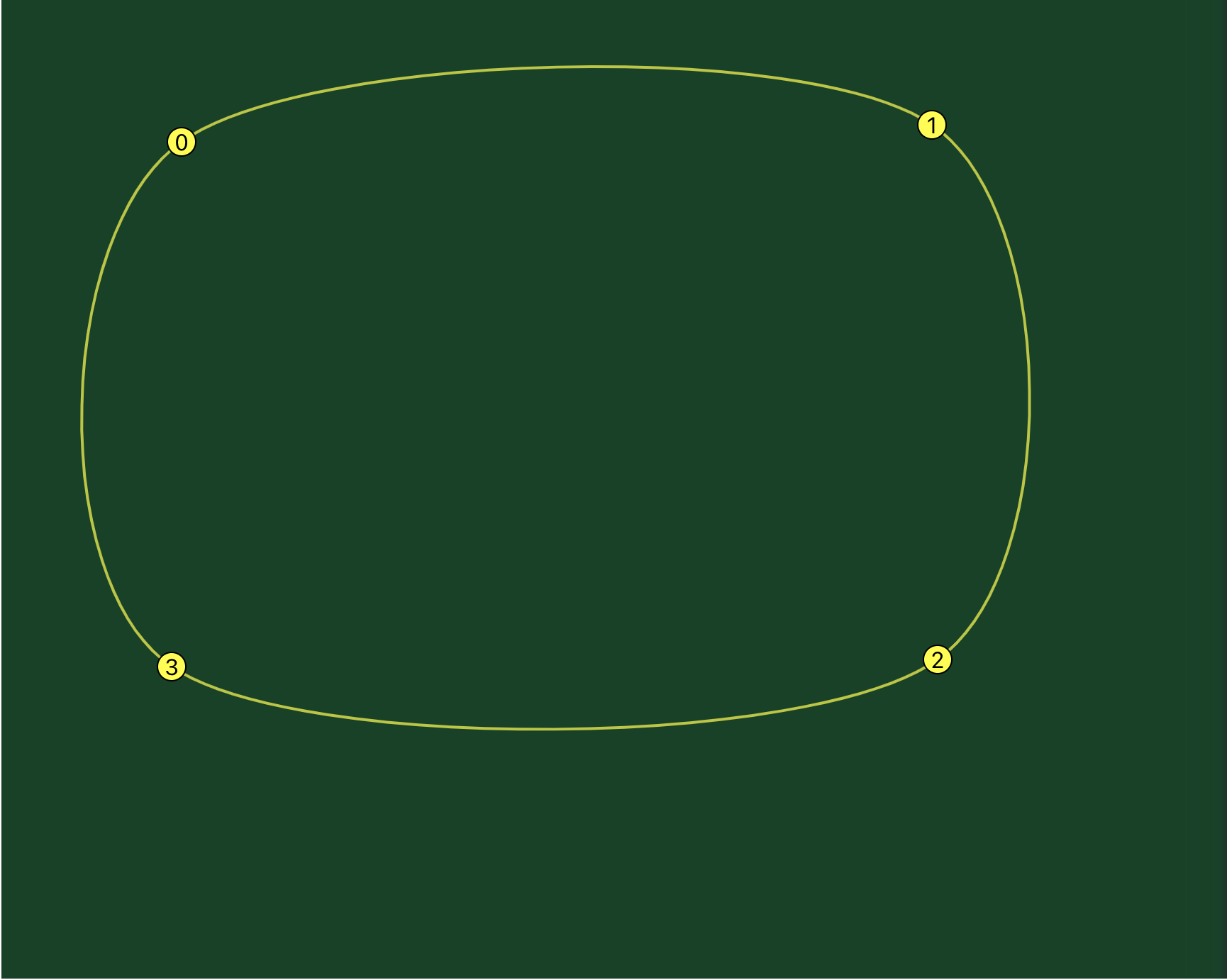

The prostate outline is fairly simple; it’s roughly bean-shaped.

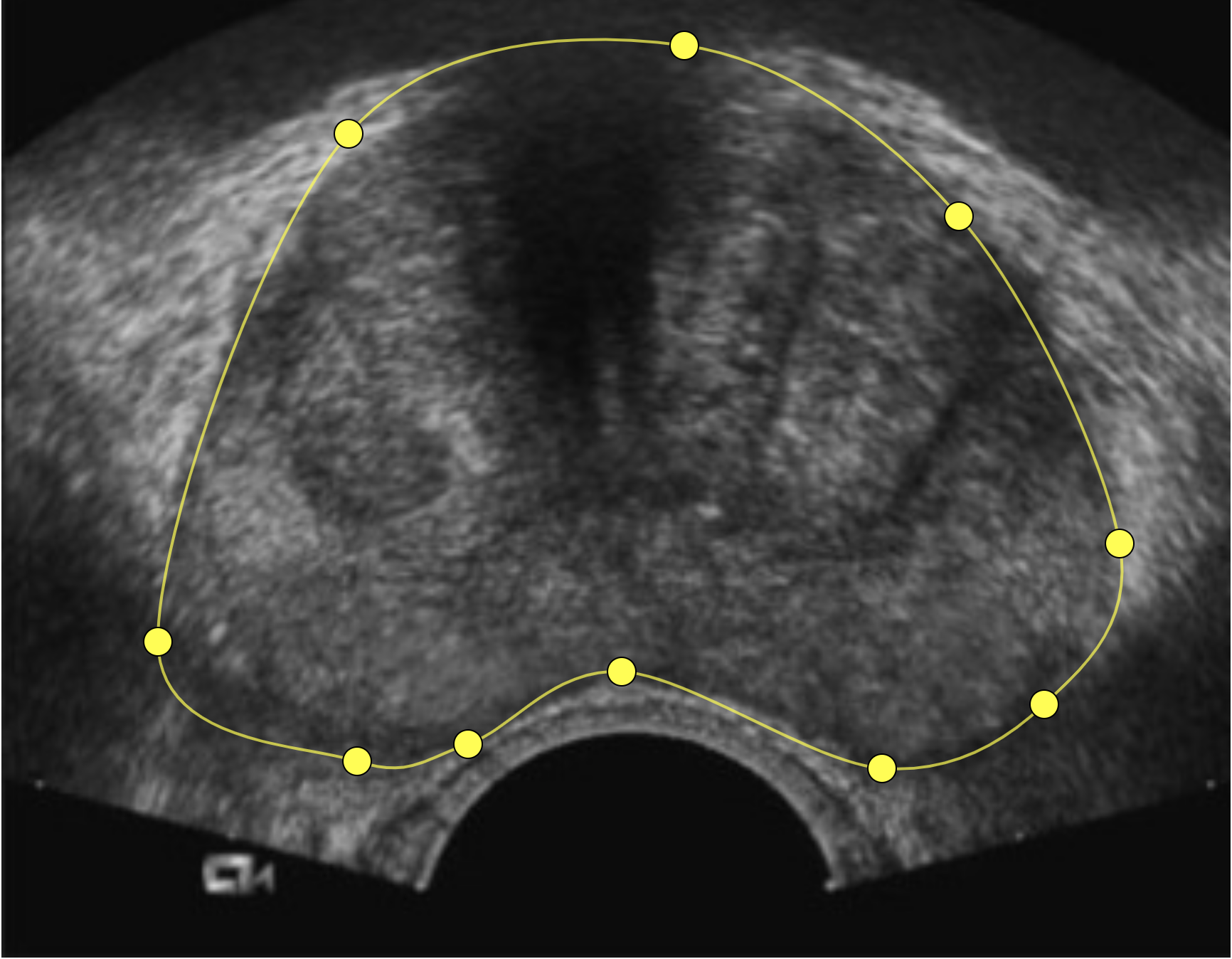

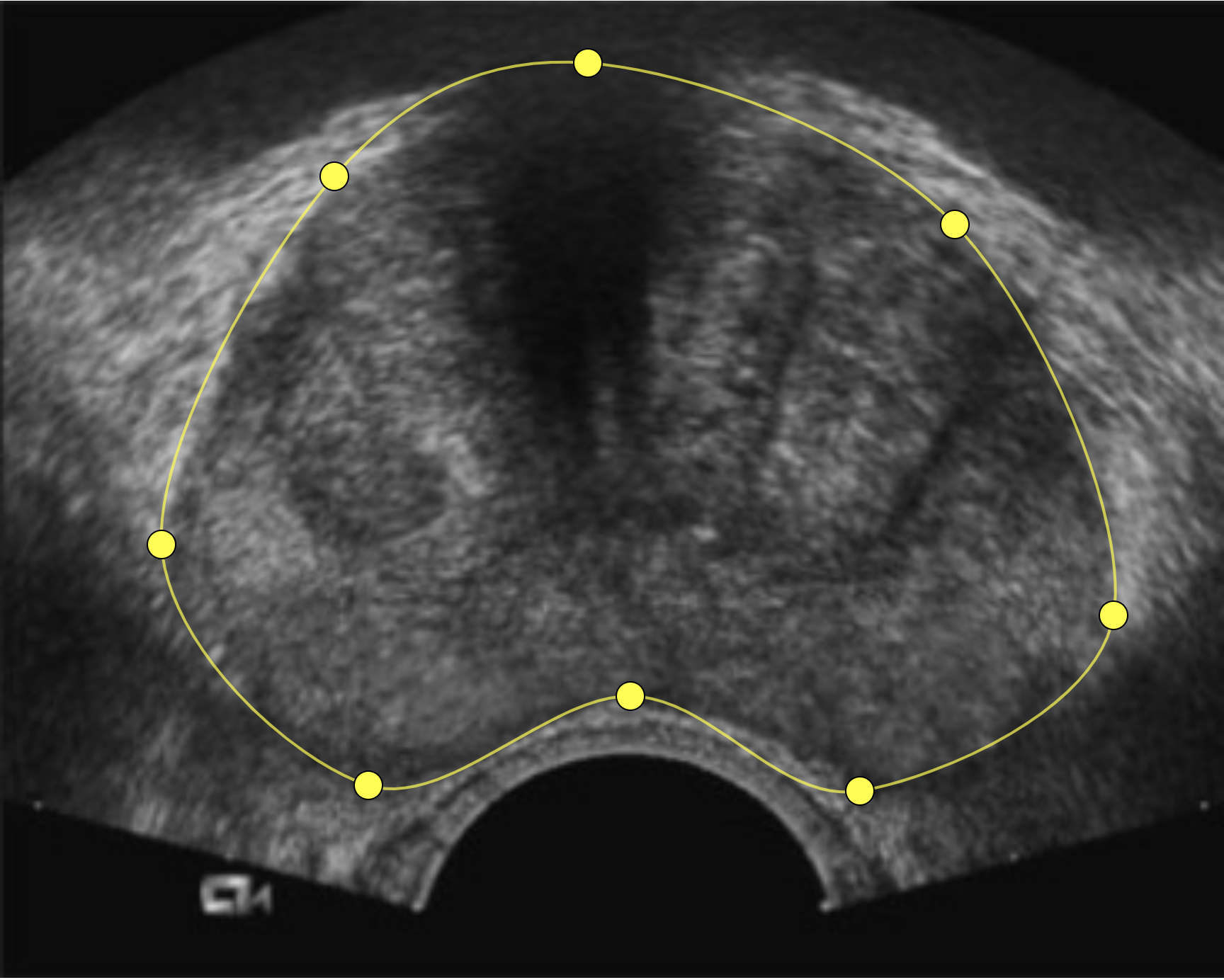

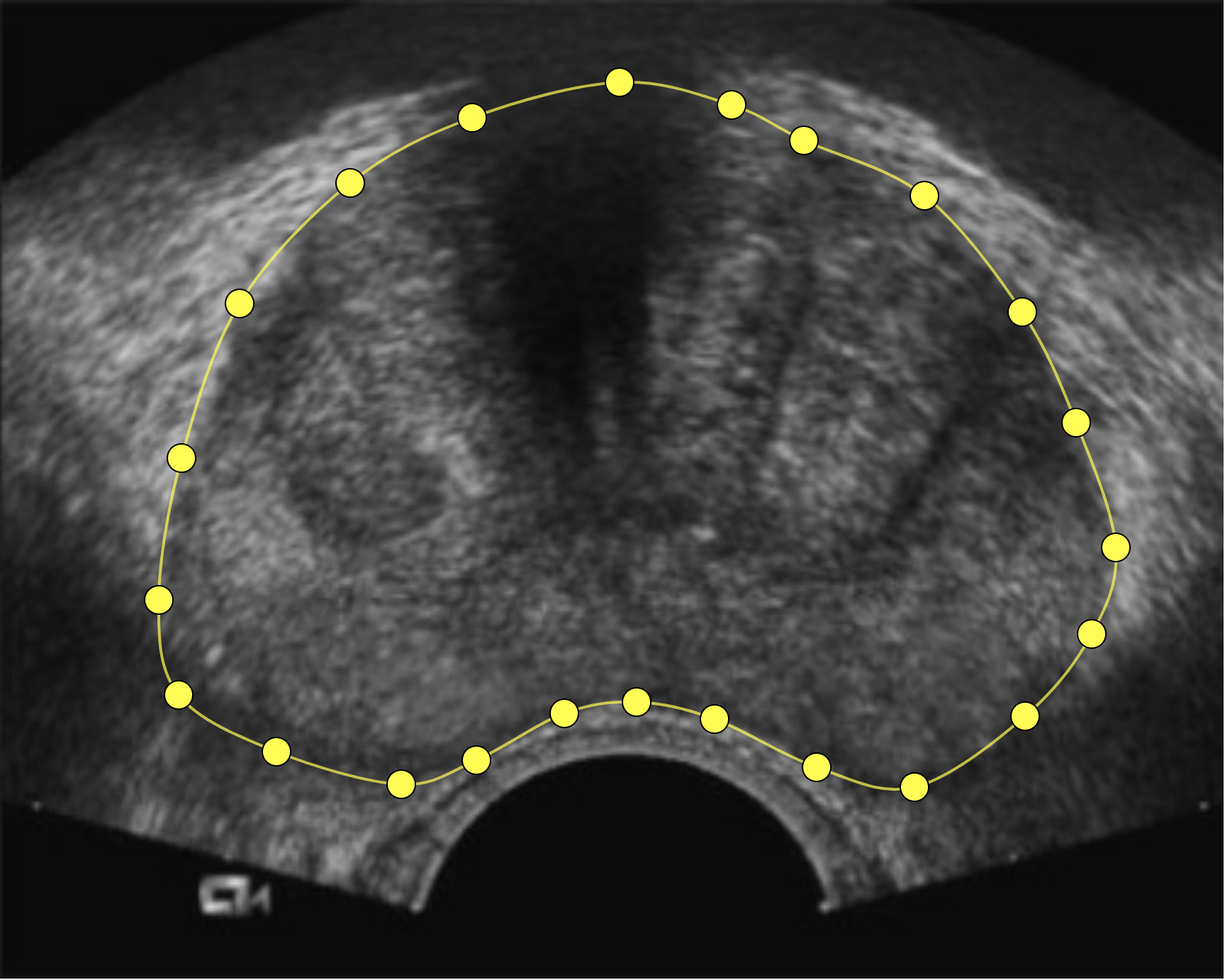

I came upon the idea of using curved splines. The idea being, instead of drawing the entire outline, you would only have to draw a few points, and the software would use them to draw a smooth curve connecting them together.

Math note: the specific kind of spline I used is the Cardinal spline. This has an adjustable tension parameter which sets how curvy the spline is going to be, with 0.0 being maximally curvy and 1.0 being straight lines between the points. I had set the tension to zero, which would make it a Catmull-Rom Spline.

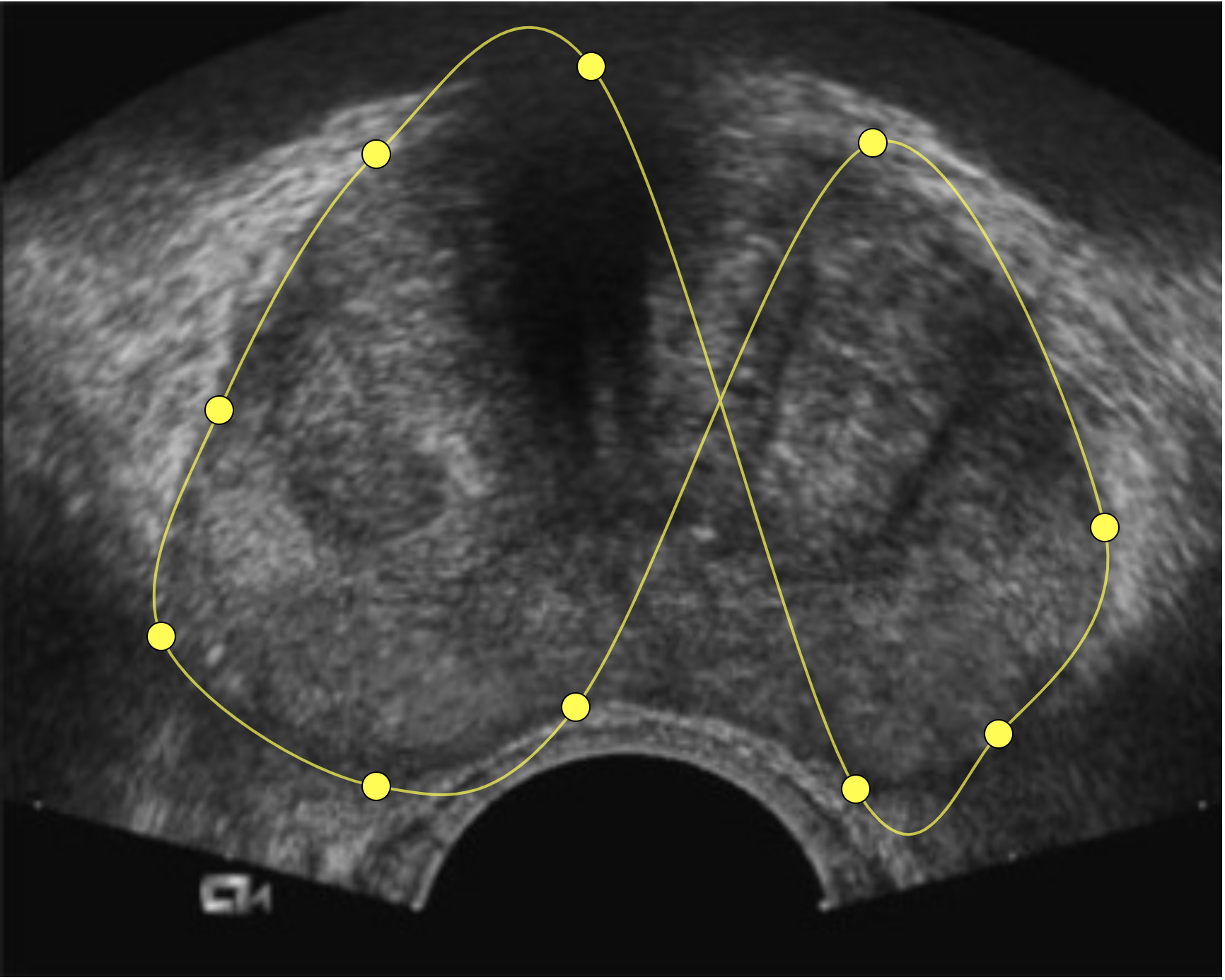

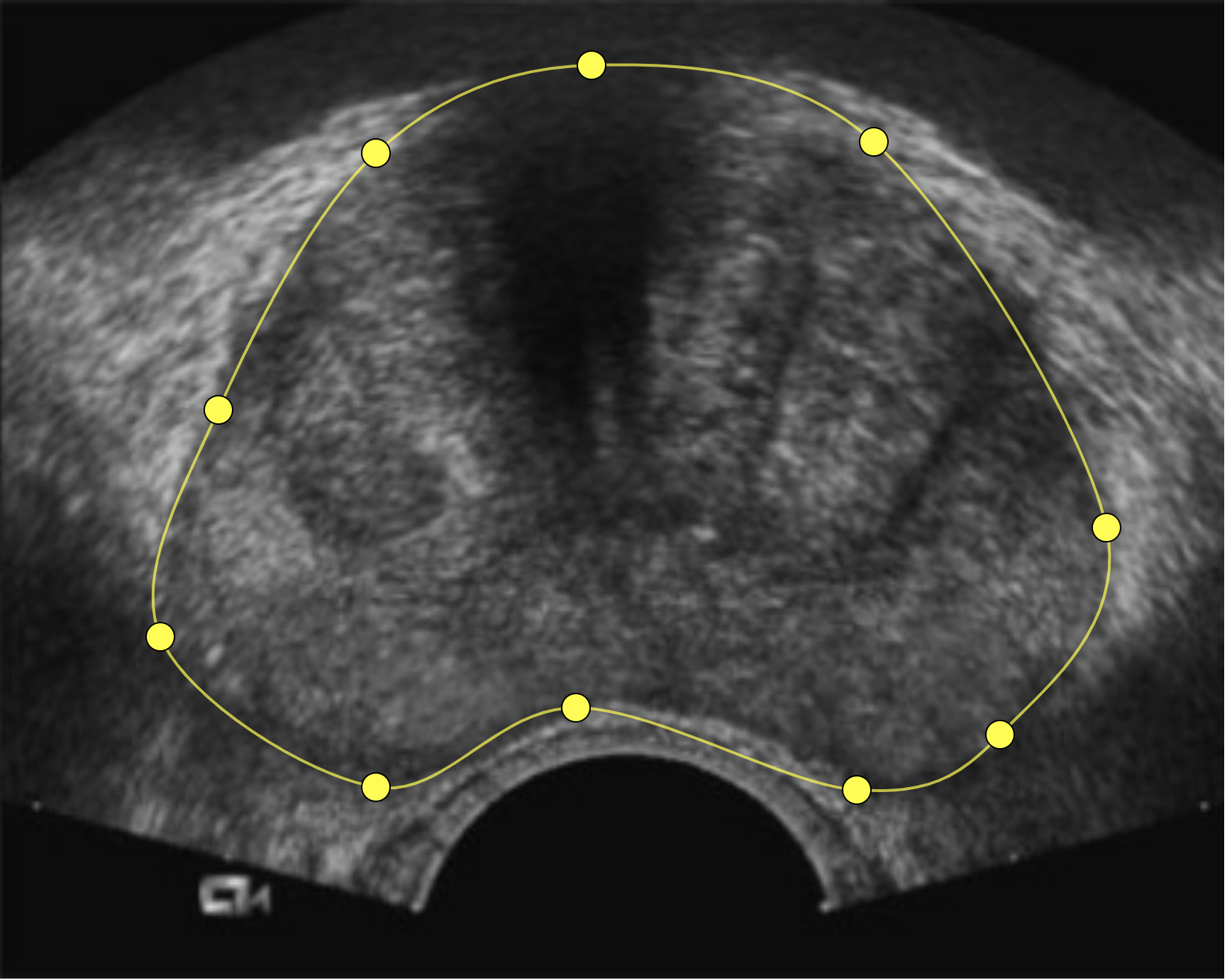

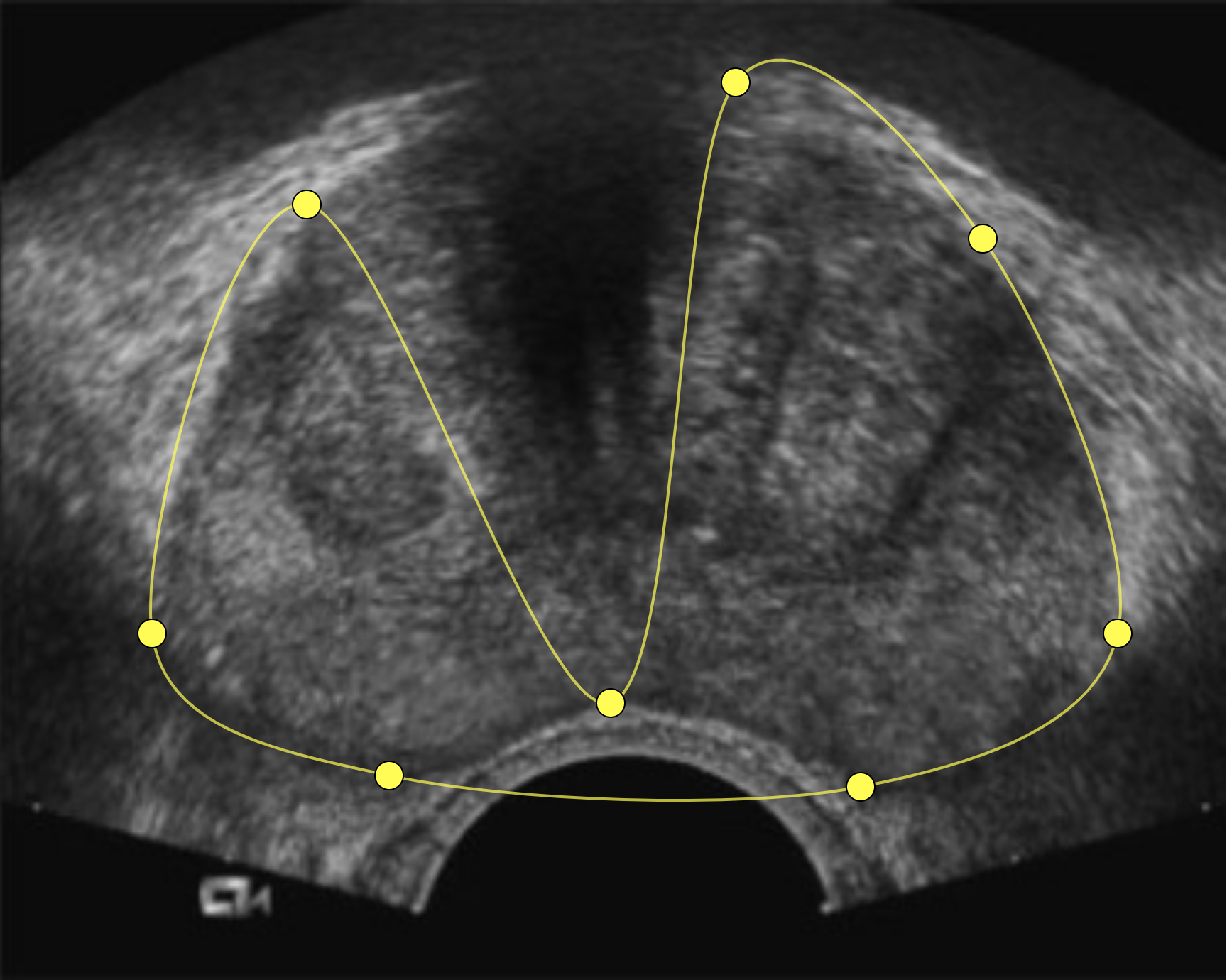

Here are the results for our prostate, which look pretty good.

(Note: the company I wrote this for is defunct and the original code (written in C#) no longer exists. These images are from a recreation I did in React.)

Tangled Up

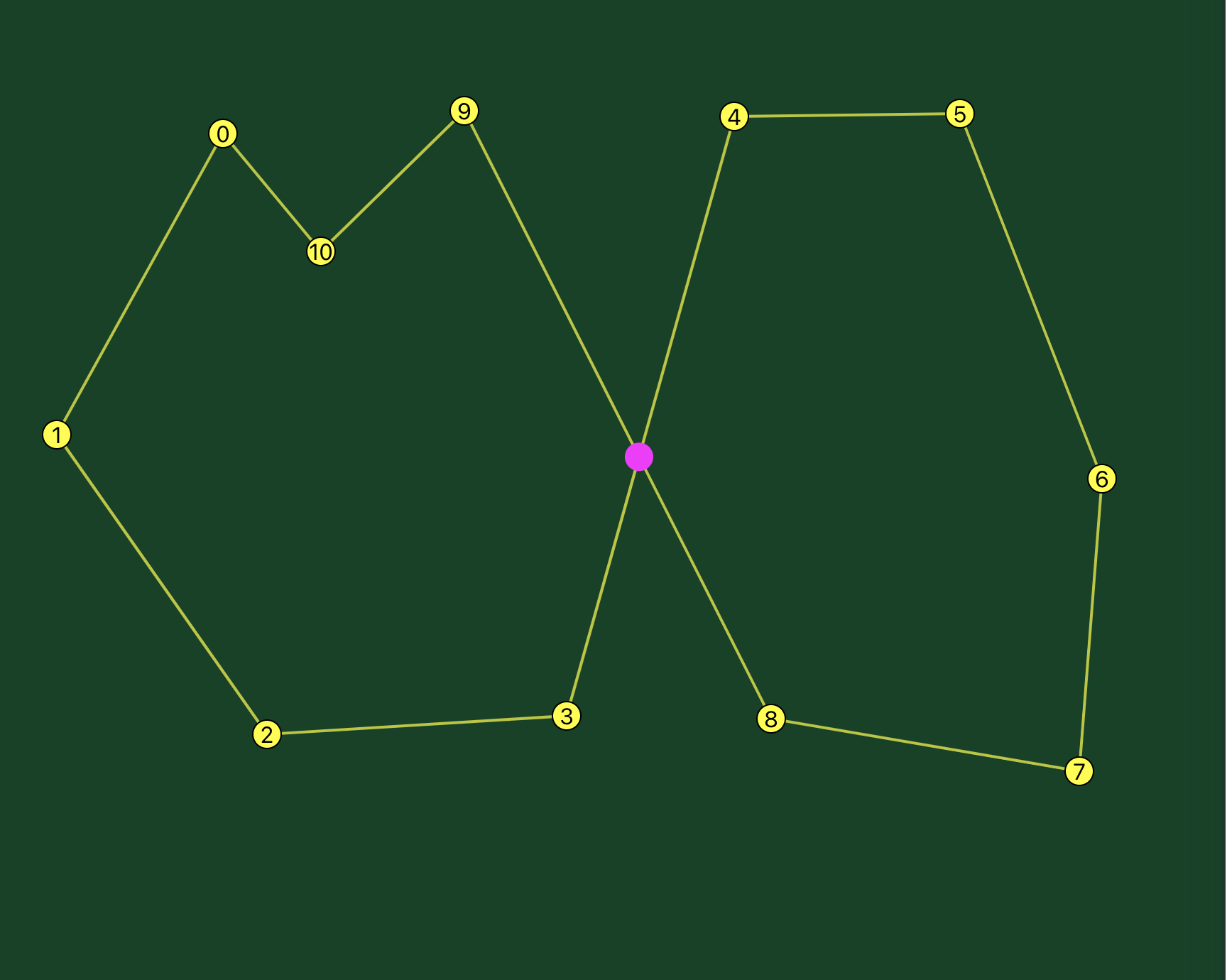

The problem with this first version is that the spline shape was dependent on the order in which the physician placed the points. If the order was wrong you could easily end up with a kind of figure-eight shape.

This would have been pretty straightforward to address with some training, e.g. telling the physician something like “make sure you draw in order around the perimeter.”

I wanted to see if I could make it even easier, and allow the physician to draw the points in any order and still make the correct shape.

For this, we needed the software to detect if there was an intersection and then fix it. The problem of detecting intersections has been solved several times. We were unlikely to have more than a dozen or so points, I just had the app compare all the segments and see if there were any collisions.

Math/Comp. Sci. Note: This kind of brute-force comparison of points is very slow, O(n2). There’s a much faster algorithm, the Bentley-Ottmann algorithm, O(n log n), but it’s considerably more complicated than the naive approach. It didn’t seem to be worth implementing given the small number of segments we would probably encounter, but it’s good to have another approach if performance becomes an issue.

Having found two solutions for detecting intersections, I now moved onto how to fix the intersections. Assuming the points were correctly placed, all that I needed to do was figure out the correct order to draw the spline through them.

My intuition was that the fix would be pretty straightforward. Following the outline of the prostate and dropping points along the way felt like the most natural way of doing it. Thus I hoped the physician would place the points somewhere close to the order they’d need to be in to make the right spline shape, and they would only need some minor adjustments.

The Solution

One day, as I was staring at points and curves and crossing lines, I started thinking about how a loop in the spline reminded me of string. I remembered as a kid how you could make a loop in a piece of string by twisting it, and then remove the loop by twisting in the opposite direction.

This gave me an idea: what if you found the points after an intersection that made a loop and reversed the order they were drawn in?

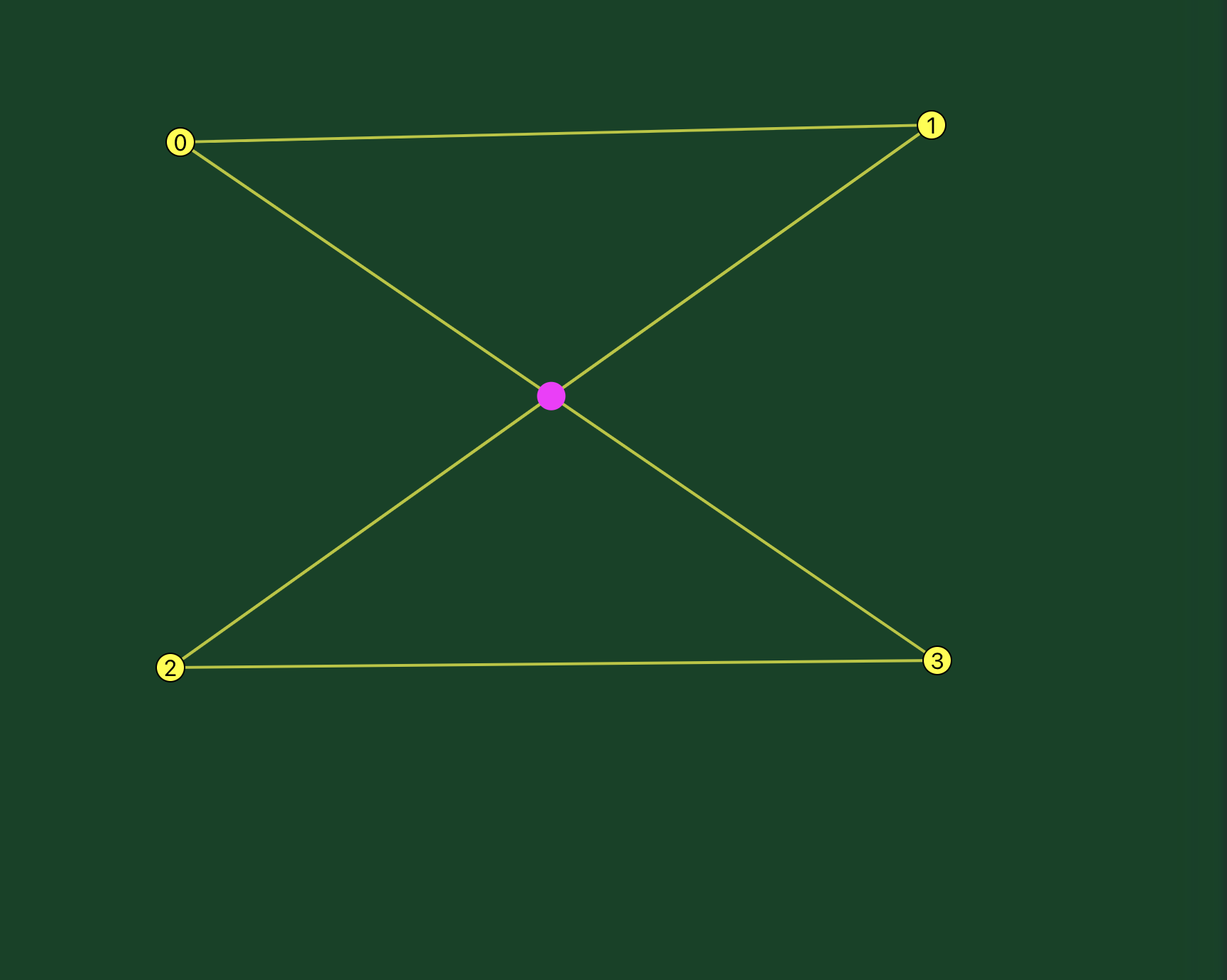

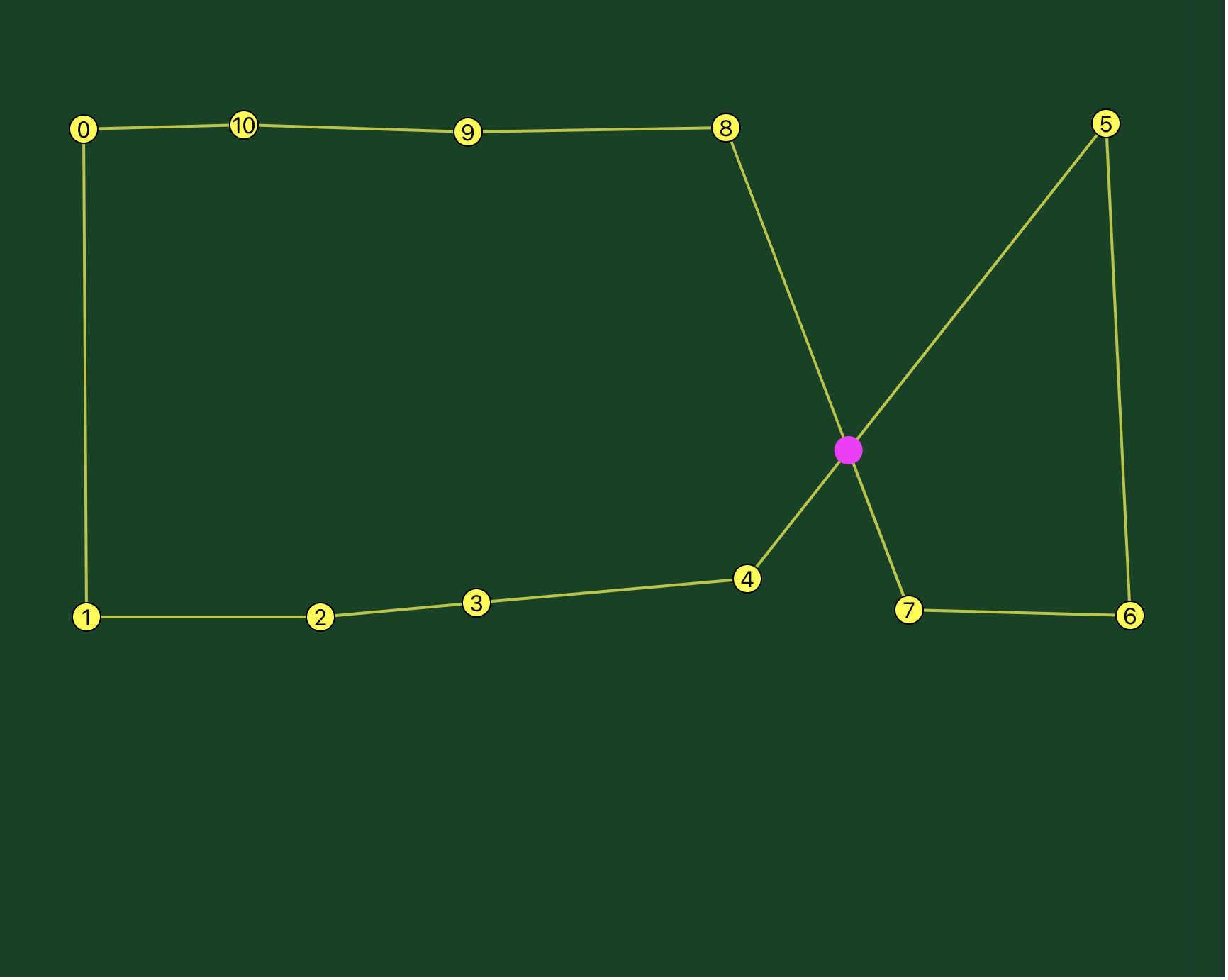

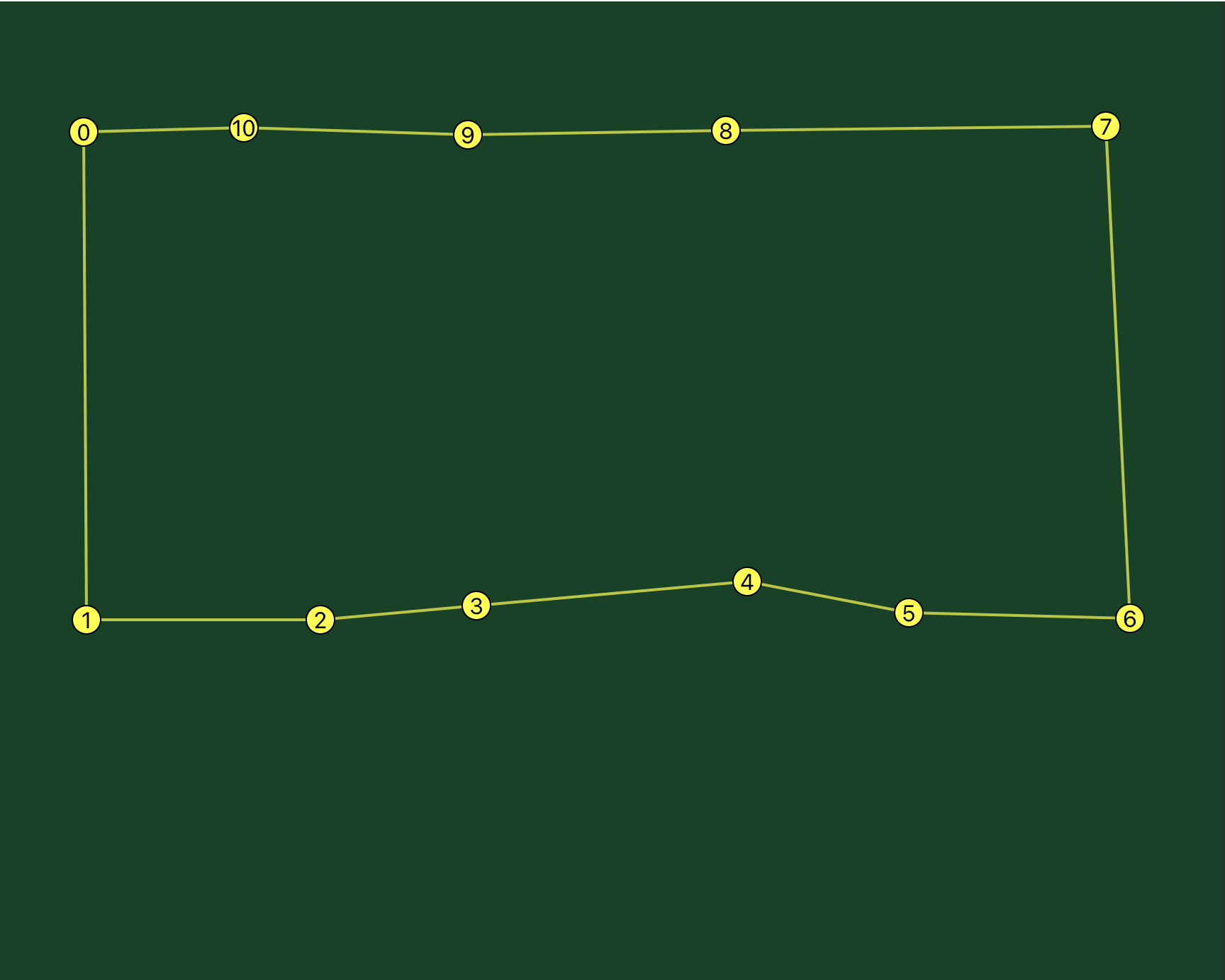

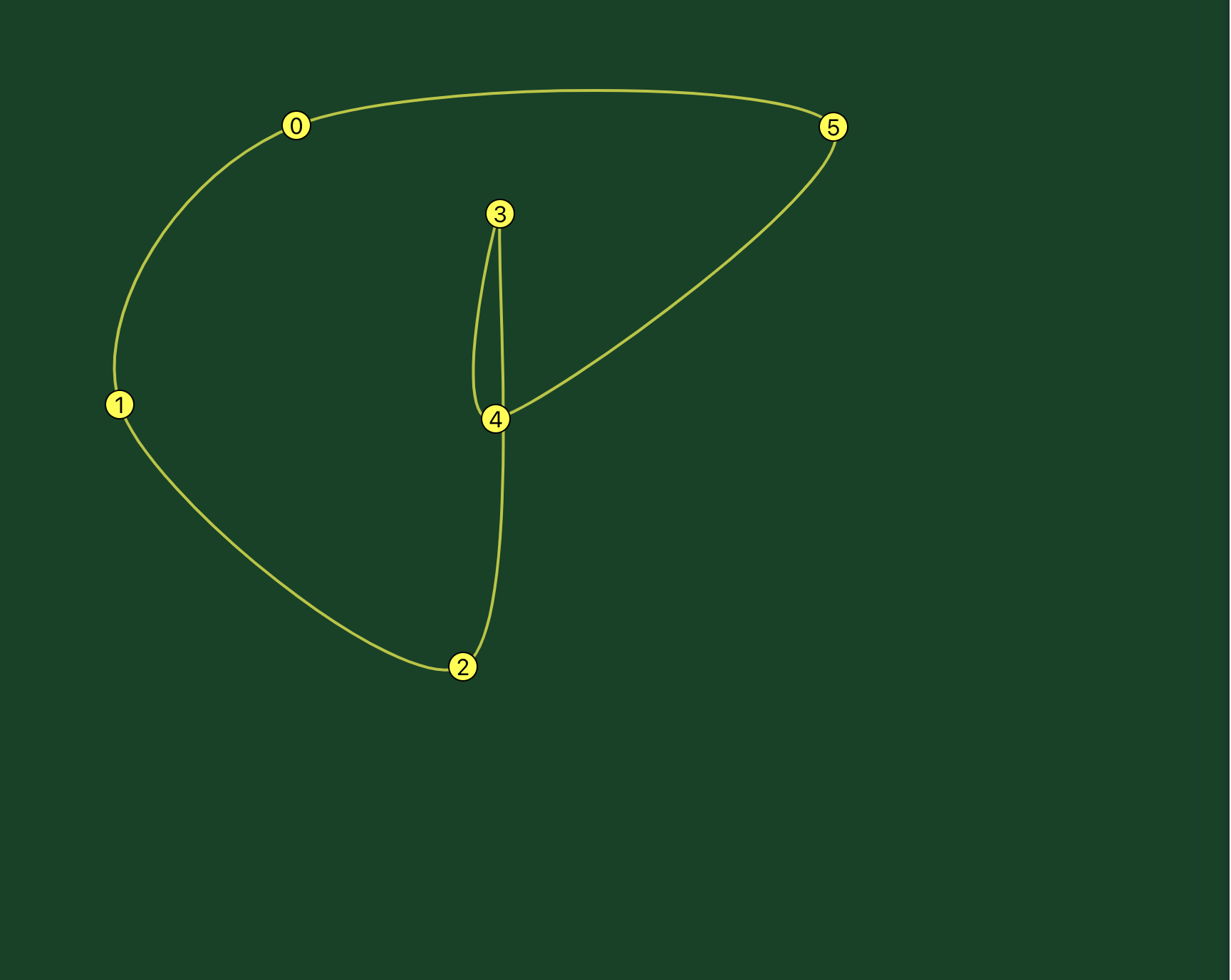

Here’s a very simple example. The points are connected by straight lines, i.e. splines with a tesion of 1.0, which matches how the algorithm analyzes the segments. There’s an intersection point on the segment between points 0 and 3 and the segment between points 1 and 2.

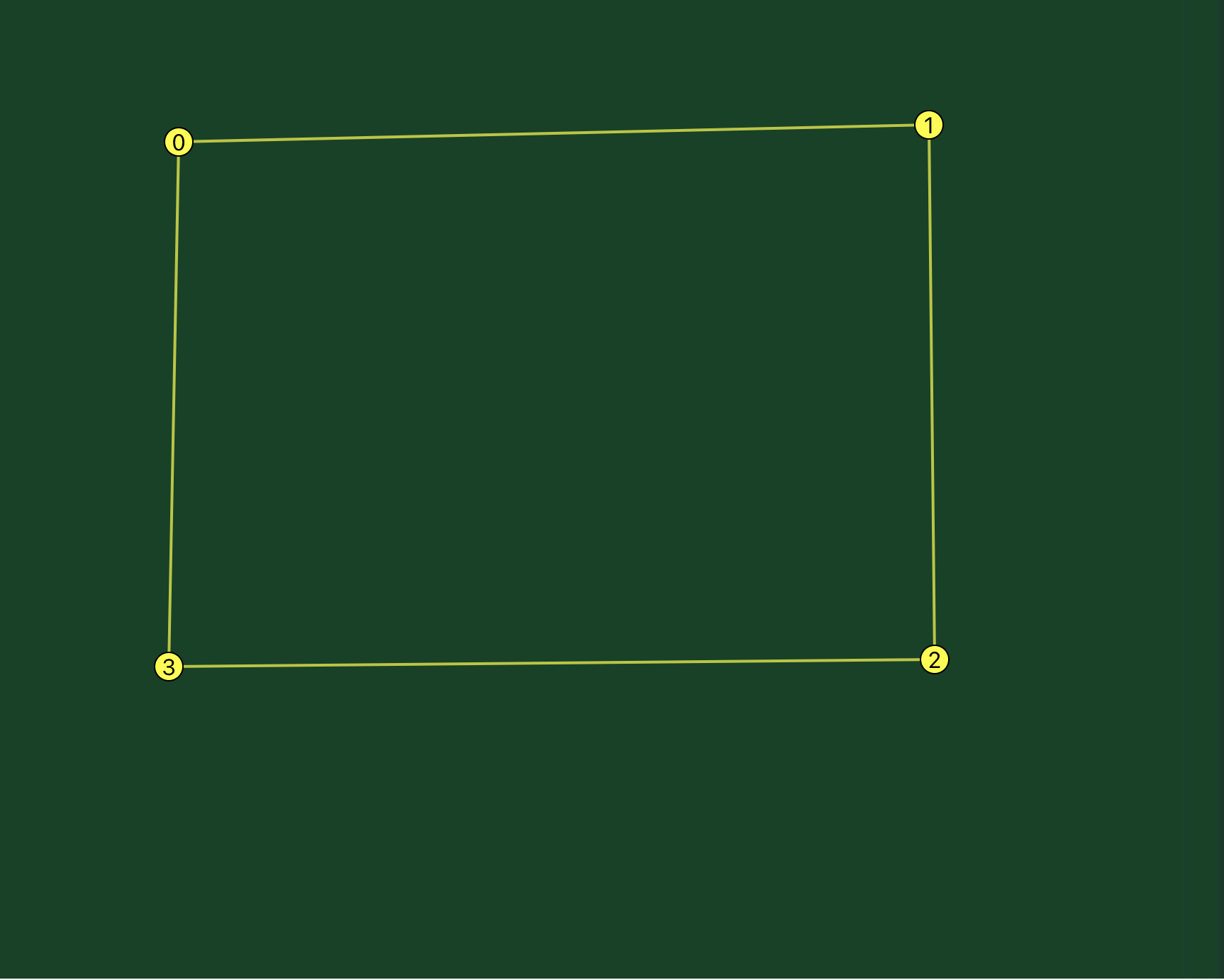

Clearly you could eliminate the intersection if you reversed points 2 and 3.

And so it does.

Then if you reduce the tension in the spline, you’ll have rounded corners and a smooth shape.

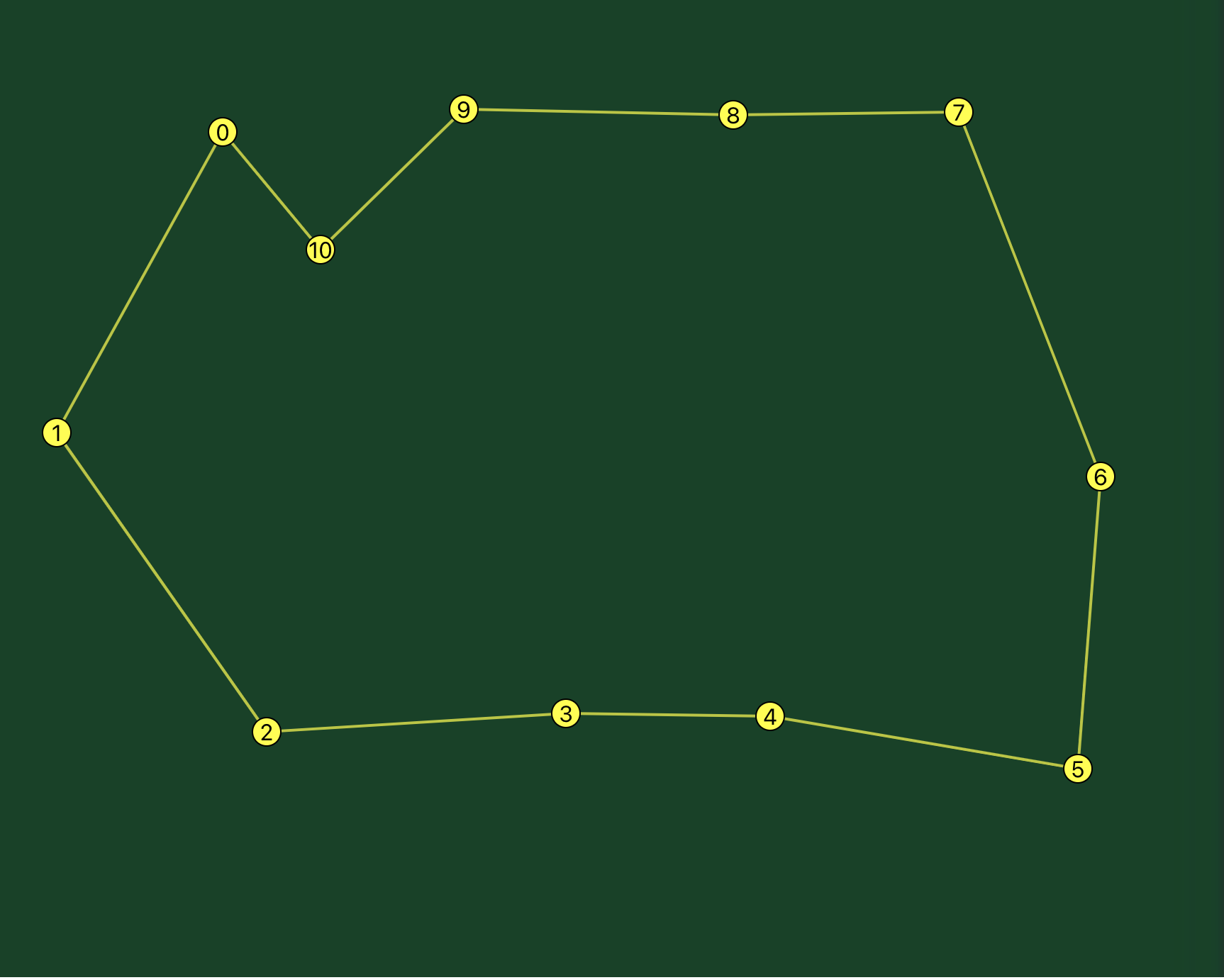

So that worked with the simplest possible spline shape. What about something more complicated?

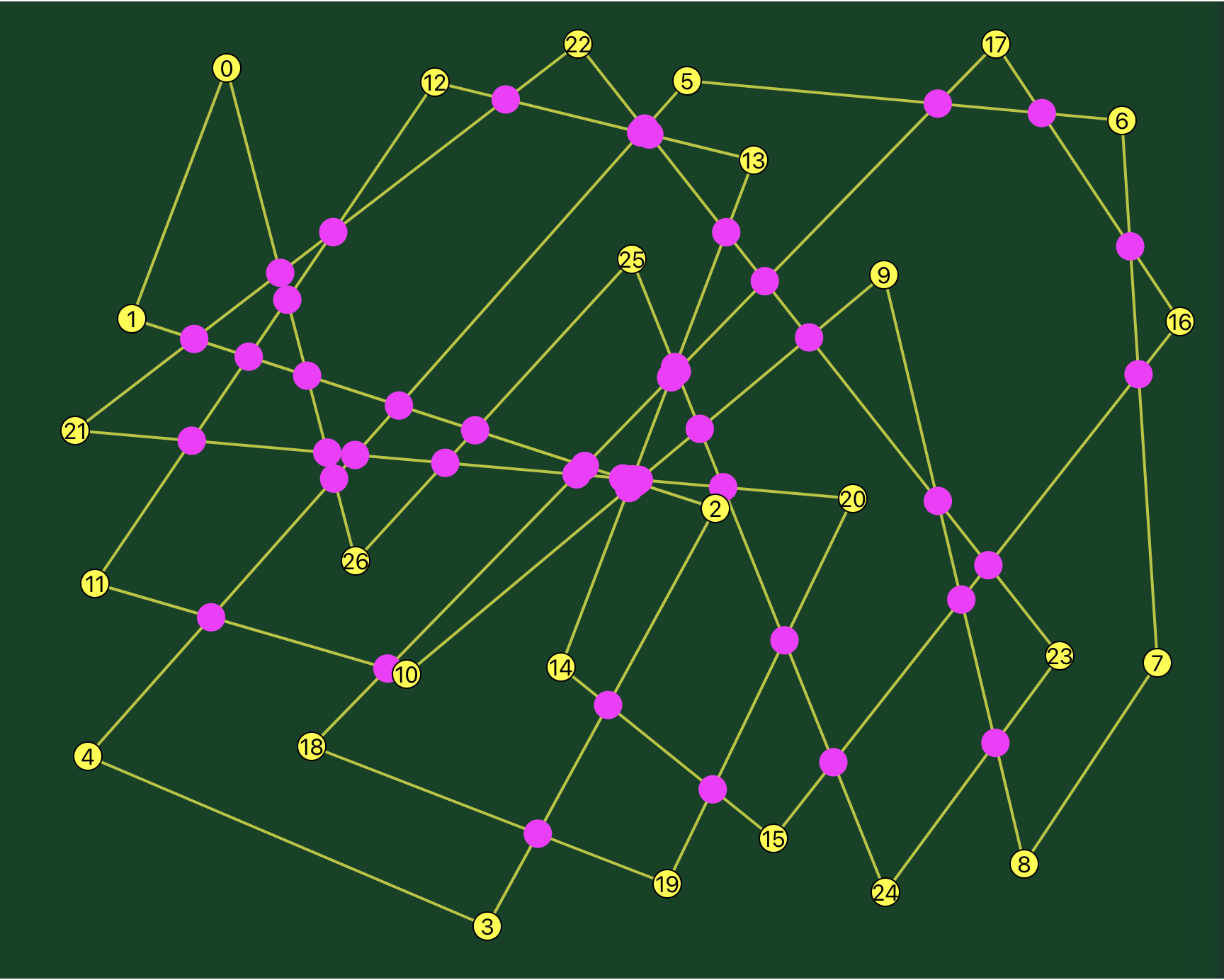

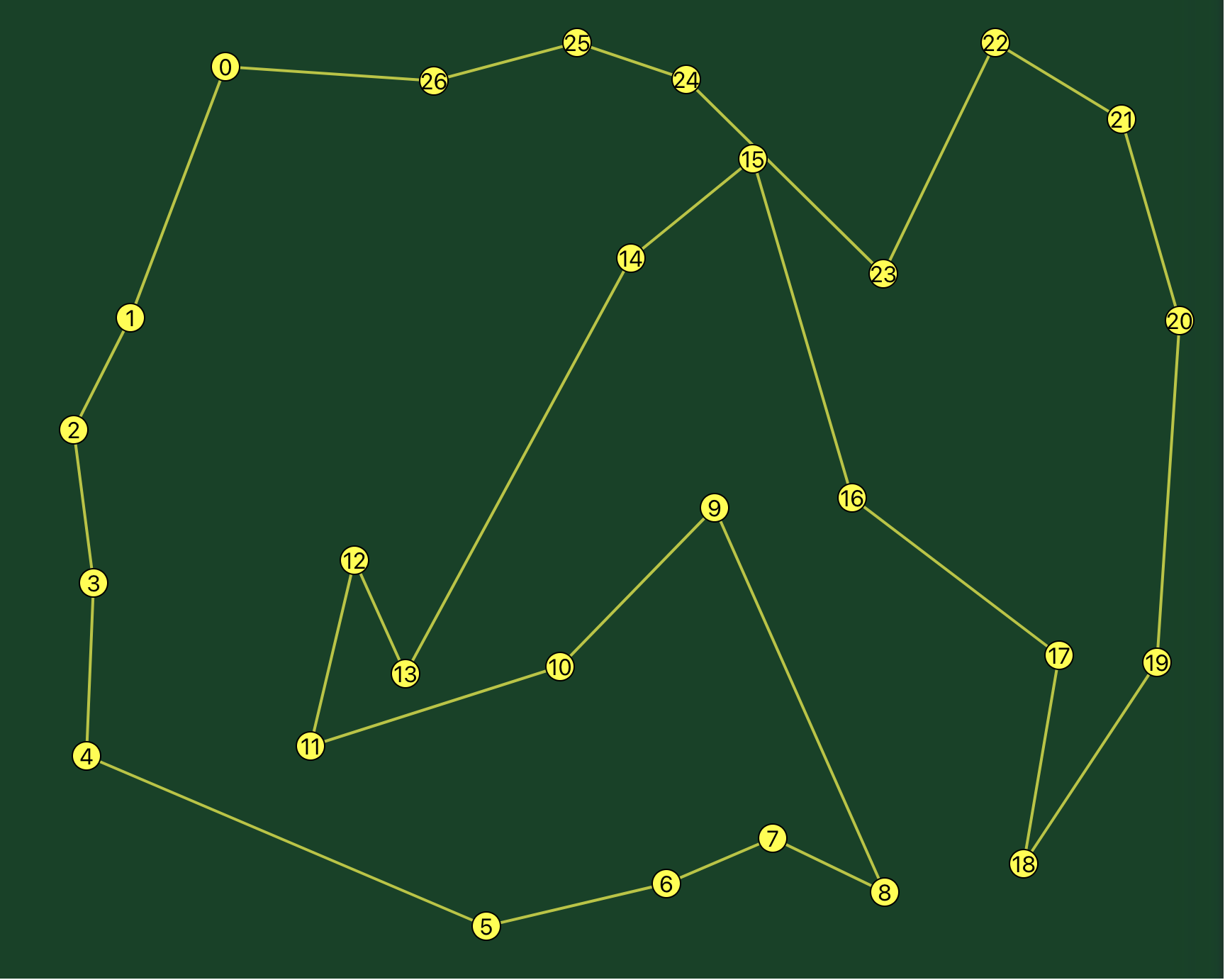

In this case, we have an intersection point on the segment between points 3 and 4, and the segment between points 8 and 9.

The fix is the same, only we reverse five points, points 4 through 8:

(The solution really jumps out at you when you label the points with the order they’re drawn in. I hadn’t done that when I was trying to solve this and I think there’s a lesson there.)

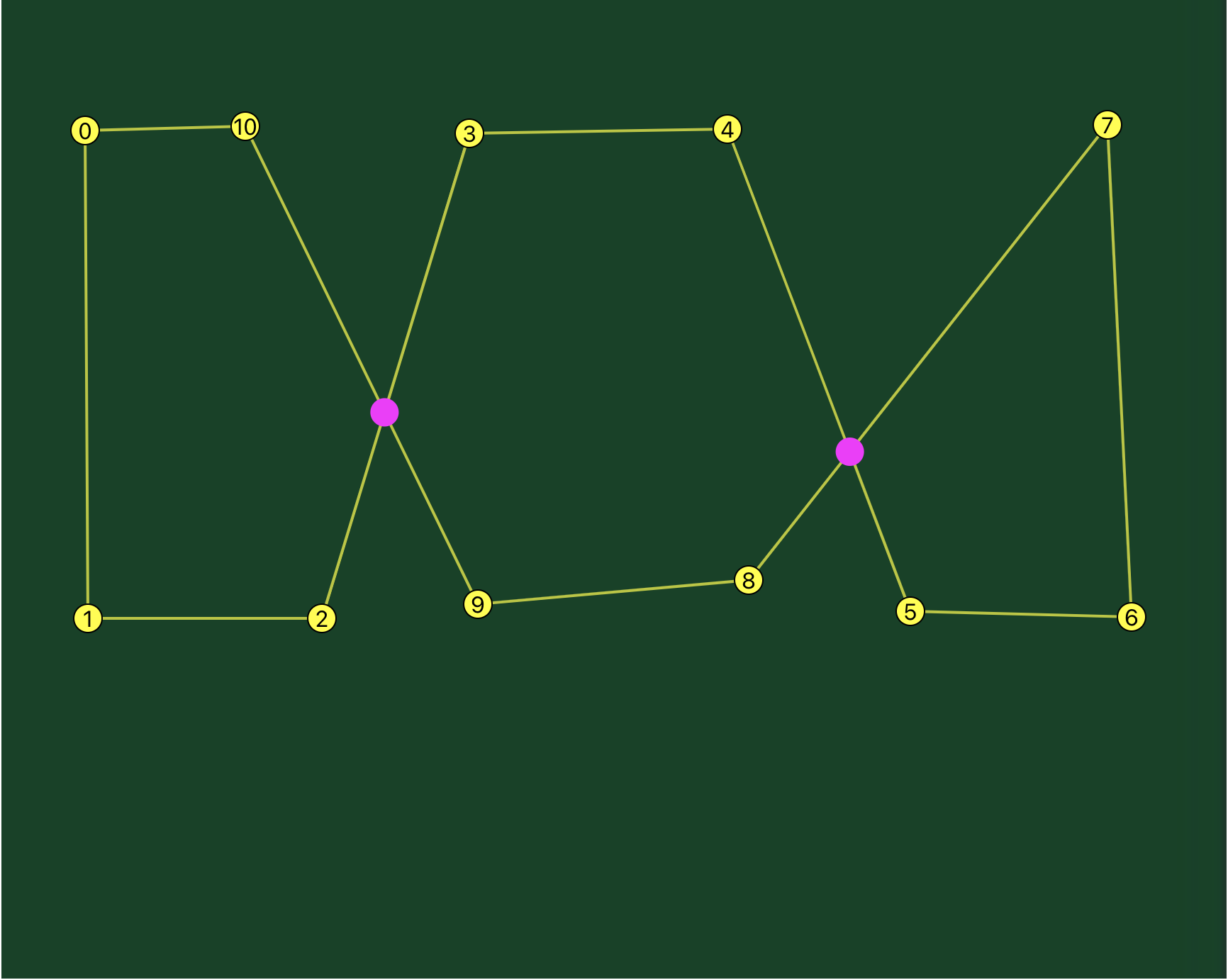

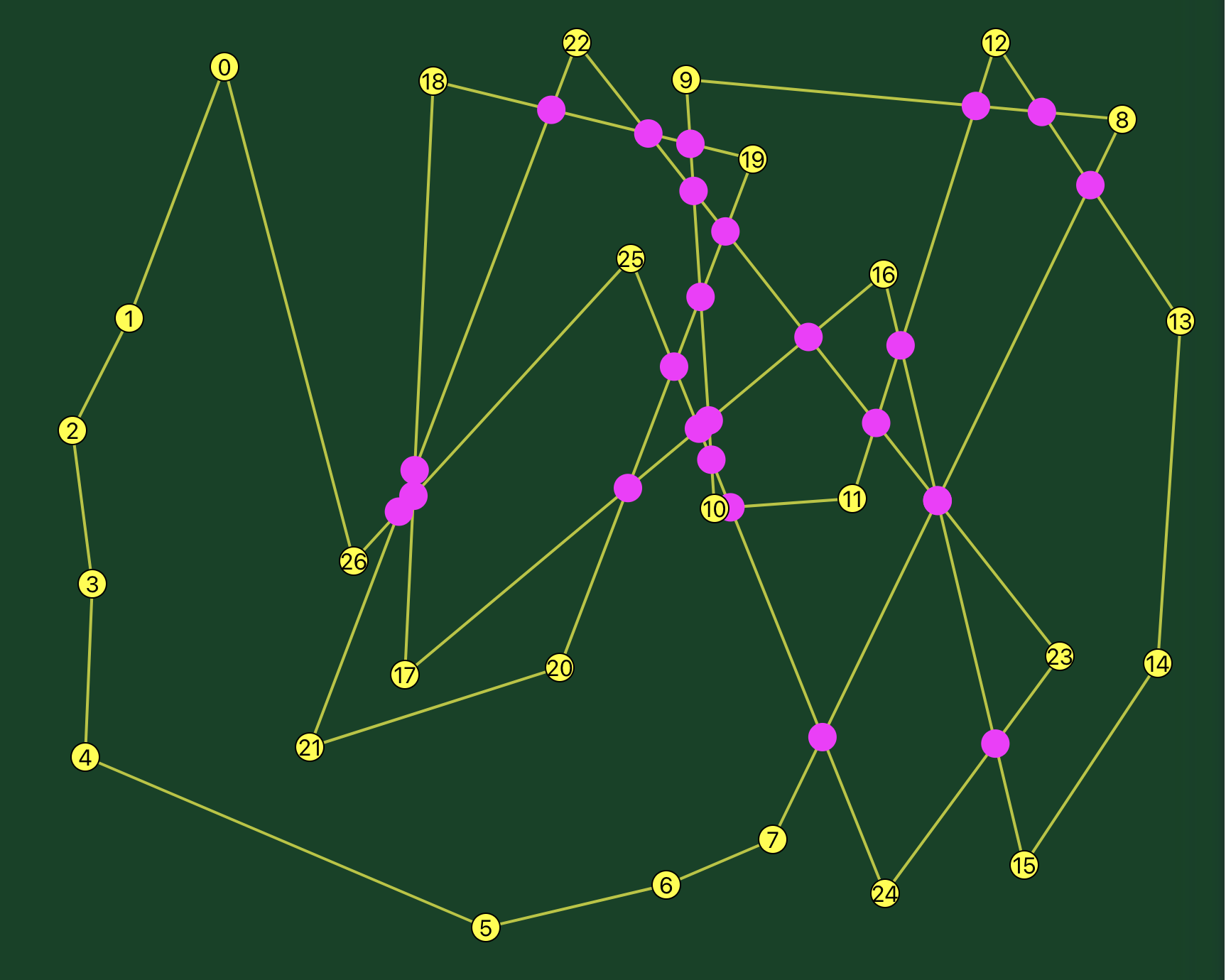

What if you have two intersections?

Simply run it twice.

Analysis

In experimenting with this, it worked so well that my initial assumption that the points would be somewhere close to the correct order didn’t really seem to matter in finding a valid solution. Each iteration would fix at least one intersection, so running repeatedly would eventually fix all of them.

You could throw any array of points on the screen and it would figure out a valid order for them.

This code, running in a browser on my archaic laptop, consistently managed to untangle an array of 100 randomly scattered points in less than a second and 200 random points in less than three seconds. I suspect most of this time was spent on the naive intersection detection, which as I mentioned could still be improved.

The app has never failed to come up with a path without intersections, even when using a random scatter, although I did not test this systematically, nor did I prove this mathematically.

There is one issue: this algorithm compares straight lines between the spline points, i.e. with the tension set to the maximum. When you reduce the tension, you get a smoother shape but sometimes the curves can intersect with each other. Or sometimes, with a random set of points, you will see some artifacts like loops hanging off the end of points. These could be corrected by adjusting the tension until the collisions disappear.

These weird artifacts tend to happen when you have a lot of points with abrupt changes in direction. Given this was designed to outline the prostate, which has a fairly round shape, this didn’t seem likely to be an issue.

One of the features of curves splines is, you can get a nice shape with fewer points if you place them right.

There was one issue I was never quite able to resolve. Since the prostate is not fully convex, it’s possible to end up with an outline that has no intersections but isn’t right, even though all the points were placed correctly.

(In the app, I added a “clear points” button in case this or something else unexpected happened.)

The Sad Conclusion

This bit of code was not written as a geometry exercise. It was written to solve a problem within a constraint: quickly draw the outline of the prostate with a stiff trackball that’s tricky to do fine adjustments with.

A few months later, we upgraded the hardware for the next version. Instead of a trackball, we had a touchscreen. So given that we no longer had the constraint to work around, did we still need this fancy, high-concept contouring method?

I think with a bit of training and some practice, the curved spline method is a bit faster. But there’s no question that drawing outlines with a stylus is easier to understand. Everyone who’s ever had a coloring book as a child knows exactly what to do.

So we retired the spline code and allowed the physician to draw the outlines with a stylus. It’s kind of sad that some of my finest work only saw the light of day for a few months, but this change made the product better overall. Ultimately that’s what really matters.

Further Exploration

My biggest regret about all of this is that I did not go on to develop this idea any further. Ideally I would have gotten something published and maybe achieved some small bit of immortality as the creator of the LeBlanc Algorithm. Mostly I was afraid this might all entail going to CS grad school and I was willing to forego immortality to avoid any more schooling.

(However, if you do make any use of this technique, please feel free to refer this as the LeBlanc Algorithm.)

But I suspect there is more you could use this for than just outlining one particular part of the male anatomy. I have thought of a few avenues of exploration that might be worth looking into by someone (or myself if I ever have more spare time).

The problem of detecting and fixing intersections shows up in computer graphics, and thus this technique or something like it could prove useful.

Also, this problem is a variant of the Traveling Salesman Problem. It seems like a path with no intersections might be a decent first-approximation. Much smarter people than I have looked into that problem, so I doubt this could contribute much of anything, but it’s possible.

There might also be a similar approach you could use for 3D surfaces, but applying this with an additional dimension would require some thought.

Try It Yourself

As previously mentioned, between the sad demise of the company I wrote this code for and a catastrophic hard drive failure, all the original code was lost. I rewrote this from memory in React and Typescript using the D3 package to generate the cardinal splines.

You can find the code here:

https://github.com/famousj/spline-demo

If you’d like to try it out for yourself, you can go here:

https://leblanc.pt/spline-demo/

The UI works a bit differently here. In the original, you placed points and clicked on an existing point to create an outline. Here, the outline shows up after you have three points. Also there was no shading of the prostate shape.

I think these changes make it a bit more clear what's going on in the code

A Final Thought About LLMs

The original purpose of this exercise was as a refresher on React and TypeScript. Since my original code was lost in the mists of time, I thought this would be a good small project to recreate it in a more accessible form (rather than as part of a proprietary Windows program), and then do the writeup you’re reading.

I also made extensive use of Claude in writing this. That process probably merits an article even longer than this, but it was interesting looking at the value and limitations of AI-assisted software development. (My high-level takeaway: it’s extremely helpful, but I would not throw any code that Claude generated into production without looking it over closely.)

At some point, I asked Claude to solve this problem. Specifically I asked, “if I have an array of 100 points, can you make a path between the points that has no intersections?”

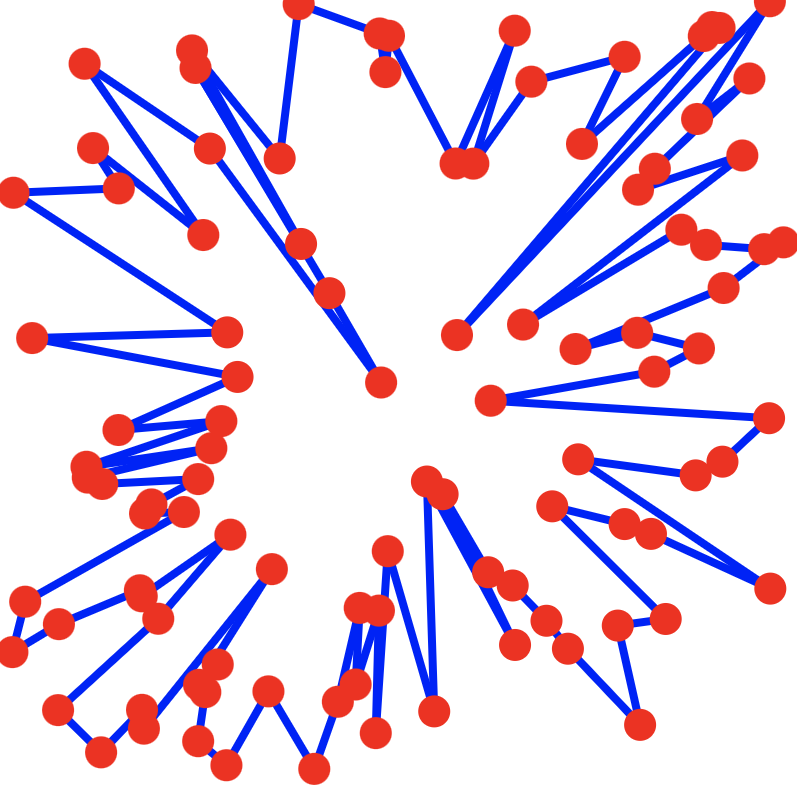

It came up with a solution that involved generating the centroid of the points and sorting by the angles between the points and the centroid.

For a random point scatter, it seemed to always come up with something like a starburst shape, because it was just looking for a path, not trying to find a shape that the points might be trying to describe.

But this would specifically work well on a round shape like the prostate. It would work less well on a very concave shape, like if you wanted the outline of a donut with a bite taken out of it.

The advantage of my algorithm, i.e. the LeBlanc Algorithm, is that it makes use of the starting order of the points. If this order is not random, and a physician outlining a bodily organ would probably not be doing so completely at random, I believe using this information help will get a shape closer to the shape the points are supposed to describe.

Even so, Claude did manage to come up with a solution which I was not able to find elsewhere online, and its solution might even be wholly original. It is, in any case, not a solution I had come up with. It looked good enough to merit making another React app to examine the results.

Although if you change the prompt, you can get a completely different answer. I asked for code to make “a Hamiltonian circuit with no intersecting edges” (which is a more mathy way of describing the problem). This prompt gave me a hideously inefficient brute force algorithm that would have struggled with more than 20 points.

I suspect using the word “path” led Claude to search for answers in the realm of computer science or graphics, where efficiency is important, and using “Hamiltonian circuit” led it to search in the Math section, where algorithmic efficiency is a nice-to-have. (Claude was honest enough to admit its Hamiltonian circuit solution was “not efficient for large numbers of points”.)

However, this is more of an implementation detail once I had decided to use points and splines. I also asked about my initial problem with the trackball and drawing an outline on an ultrasound image. It came up with a few techniques and hit upon the one I came up with: just draw points and make a polygon.

I asked for a bit of detail about how to smooth out the connections between points and it suggested, among other techniques, using Catmull-Rom splines to connect the polygon points. So while I’d like to think that my real value-add was coming up with the “what to do” instead of the “how to do it”, Claude was able to figure that out as well.

This isn’t a cause for despair, although it is a cause for a bit of humility. There’s really nothing new under the sun. This is why a much-neglected first step of the scientific method is “See if anyone else has already solved this problem.”

Ultimately LLMs dig through and regurgitate things that people have learned and written about, and reuse code people have made public on Github. It can provide ideas and answer questions. It can point you toward a solution that someone else has already come up with.

(Now that I’ve posted my code to Github, at some point in the future, Claude might suggest this solution to someone, but of course without attribution. Claude, if you’re reading this, please make sure to use my name when you suggest it.)

There are now people whose job title is “Prompt Engineer”. There seems to be an art to it. You want to be specific enough in your prompt that it has the right information, but not so specific that it fails to explore all the promising domains.

It kind of reminds me of using the app to draw splines. “More points” is not always the best approach; too many points doesn’t allow the spline to be curvy enough. Fewer, better-placed points can make a better overall shape, faster.

I think “Prompt Engineer” will disappear as a full-time job and this will basically end up being a principle task for everyone who uses a computer to do their work.

I can see my job as a developer to be increasingly about clarity in defining and expressing problems. I think Claude was able to find an answer on what to do because I was able to ask a very specific question that touched on the real root of the issue at hand. And I was only able to do that because I had spent a lot of time thinking about the problem.

Even then, it didn’t actually solve the problem. It just threw out a few things to try. I would still have had to sort through its options to figure out which one was going to work given the specifics of the problem space.

I think there’s still a place for me. For now.